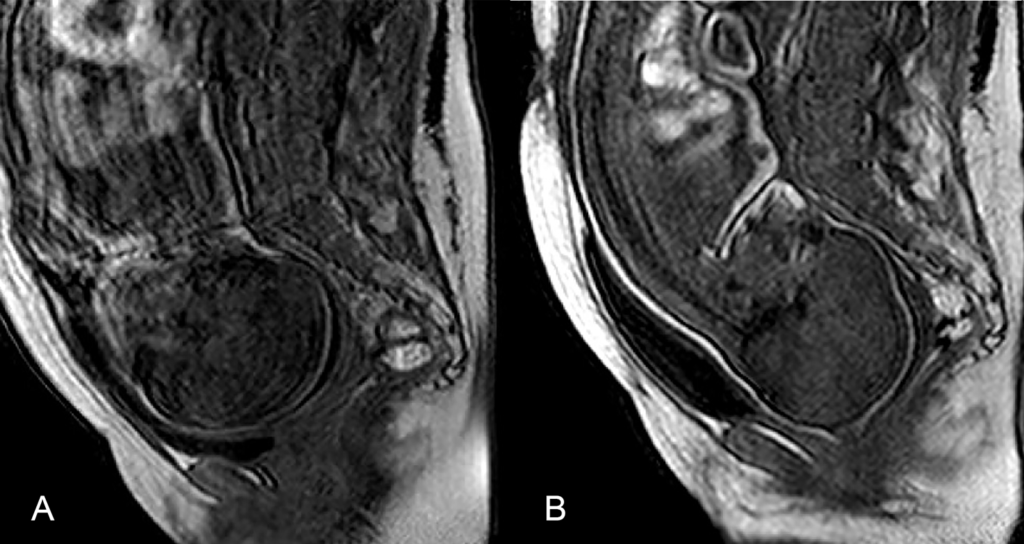

It seems obvious to assume that a baby’s head gets squished as it’s pushed through the birth canal, but we could only really speculate. Now, a new study reveals mind-boggling images of babies inside their mothers as they’re being born.

The research team, led by Olivier Ami at the University of Clermont Auvergne, in France, performed 3D Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) on seven pregnant women before they went into labour and then just before birth, when they got ready to start pushing (active labour). After the scan the moms-to-be were quickly moved back to the delivery ward to give birth.

A squash and a squeeze

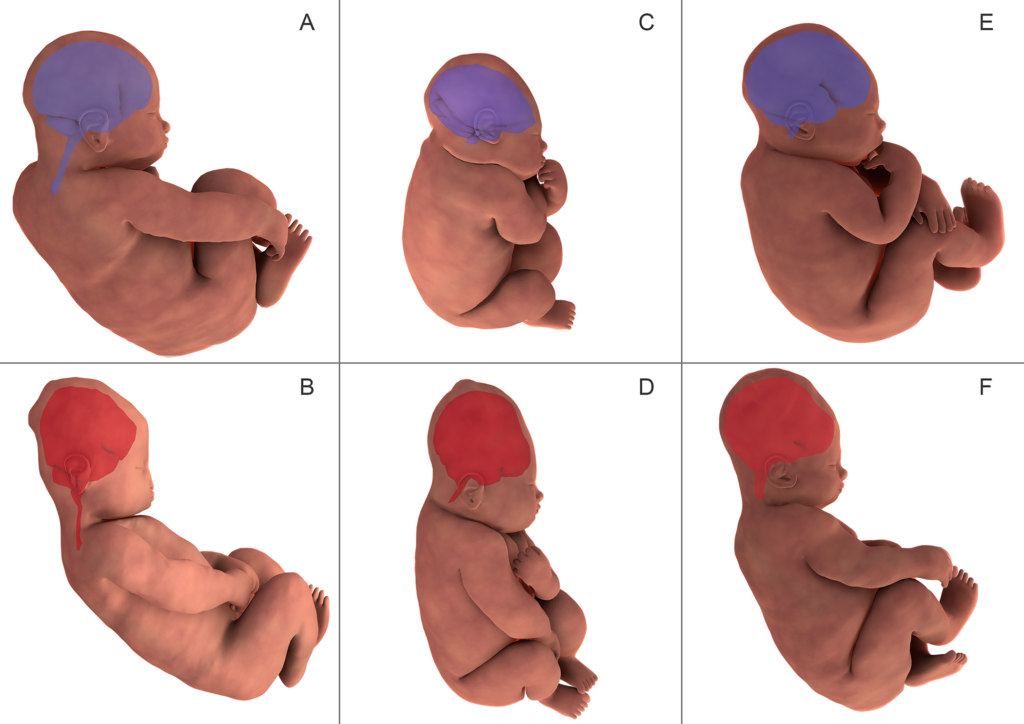

Babies’ heads can change shape because the skull is made of several bones with gaps between them, just like a puzzle. These gaps (called fontanels) allow the skull bones to slide and overlap on top of one another, which reduces the overall size the head. Ami and colleagues now show just how much a baby’s head (and brain) gets squeezed during birth.

The detailed 3D digital reconstructions of the MRI scans showed that all the babies started off with a normal roundish head, but as they moved down the birth canal their heads became squished and deformed to various degrees. The researchers also found that babies are under much more stress during birth than previously thought, but for most of them the heads went back to normal immediately after birth. Only two babies retained the ‘peanut’-shaped head for some time, but they were happy, healthy babies nonetheless.

The baby with the worst head deformation, which was also the largest baby, had the lowest health APGAR score a minute after birth, even though the mother seemed to have a normal and quick (almost effortless) delivery. How come was the baby poorly then? The baby was out quickly and yet took longer to recover from birth… The authors suspect this baby was in distress because the head squishing was so severe, which raises an important question: is our definition of an ‘easy delivery’ accurate? Probably not.

The other two babies with severe head distortion weren’t well positioned in the birth canal and ended up being delivered by emergency cesarean. Coincidence? It’s likely that extreme changes in head shape are linked to a longer recovery from birth and difficult deliveries (even when they’re quick), but larger studies with more babies are needed to confirm this.

Does head deformation during birth cause brain damage?

A common concern is whether this so-called foetal head moulding can cause brain damage, but parents can be reassured because the brain is very well protected from external pressure forces during labour. Although about 40% of babies delivered vaginally show signs of brain compression at birth (bleeding in the eyes or brain), to date there’s no evidence they suffer any long-term brain damage. Even so, Ami and colleagues want to look into this in more detail with MRI technology, because newborns that appear healthy could still have brain haemorrhages. To study the health consequences of extreme head distortion, the team plans to use MRI in combination with a blood test for a common biomarker of traumatic brain injury.

But there are other risks. Difficult deliveries can be traumatic for both mother and baby, and they’re nearly impossible to predict. Large babies are associated with a higher risk of emergency cesarean, as they might get stuck at the shoulders (called shoulder dystocia), but the methods used routinely in hospitals to measure foetal size are unreliable. Ultrasounds predict baby weight with an accuracy of only 50%, meaning that over half the babies will be bigger or smaller that what was estimated, and for bigger babies ultrasound accuracy is even lower (20-30%).

Measuring the pelvis size of a pregnant woman (pelvimetry) is another method used to predict whether a baby can fight his way through the birth canal, but recent studies have claimed this practice is just a waste of time. Ami and colleagues’ MRI images put an end to this debate and show beyond any doubt that pelvimetry is unreliable- the belief that women with larger hips can give birth more easily (and the other way round) is nothing more than a myth.

A new software to predict the risk of traumatic birth

The authors believe that MRI scans can estimate baby weight more accurately than ultrasound, but for predicting the outcome of a delivery it’s the head that matters. “It is the size and geometry of the head that should be compared to the size and geometry of the birth canal”, explains Ami. But how feasible would it be to get women giving birth inside an MRI machine? This would obviously be impractical, Ami says, but he adds:

MRIs can, and probably will, be used in the hospitals in which they are available. […] We hope that a simple MRI scan performed at 37 weeks will be enough to predict all the risks until the end of pregnancy.

The authors plan to use the new MRI data to develop a delivery simulation software to better inform pregnant women on their future delivery, including whether there is a risk of traumatic birth for her or her baby. Ami concludes that “there will then be a discussion with the obstetrician or midwife to choose with the expectant mother the best delivery route in accordance with her wishes.”

References:

Olivier Ami et al. Three-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging of fetal head molding and brain shape changed during the second stage of labor. (2019) PLoSONE

Kent D. Heyborne. A Systematic Review of Intrapartum Fetal Head Compression: What Is the Impact on the Fetal Brain? (2017) American Journal of Perinatology Reports

Suneet P. Chauhan et al. Suspicion and treatment of the macrosomic fetus: a review . (2005) American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Mehreen Zaigham et al. Protein S100B in umbilical cord blood as a potential biomarker of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy in asphyxiated newborns. (2017) Early Human Development