Illustration by Catarina Moreno ([email protected])

Humans are living longer than ever before, but is there a downside to this? Over the past 15 years, dementia has become the leading cause of death globally, overtaking cancer and heart disease. The future doesn’t seem any brighter- the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates the number of deaths from dementia worldwide will nearly double by 2030.

What is dementia? The common belief is that dementia is a natural part of ageing, but in reality it’s a symptom of neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia is typically characterised by memory loss, confusion, and difficulty in language processing and communication.

What people don’t realise is that dementia is the most common cause of death […] but there’s a lot less funding to study dementia, which means there’s a lot less research.

Teresa Niccoli is a researcher at the University College London Institute for Healthy Ageing and she uses an unusual approach to study Alzheimer’s and other dementia-related diseases. We recently visited Niccoli’s lab to learn more about her exciting research and the personal challenges she faced as a woman in science (see video below).

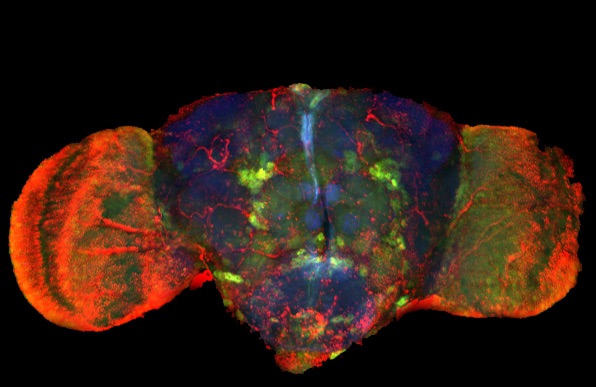

Niccoli’s lab uses the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster to investigate how specific human genes contribute to dementia. Although it might seem odd to use this pesky insect to study human disease, Drosophila is an excellent model organism to understand the basic molecular mechanisms of complex neurological disorders. To start with, flies carry about 75% of the human genes associated with disease, and they also have a complex nervous system with the same type of nerve cells (neurons) as humans. In the video, Niccoli explains her research and the many advantages of using fruit flies to study dementia (you can also learn more here about why scientists use fruit flies in their research).

A variety of fly models that mimic human diseases have been made by labs around the world, including models of cancer, cardiovascular, and neurodegenerative diseases. Researchers use these fly models to quickly (and cheaply) track down the genes and cellular pathways causing disease and to screen for new pharmaceutical drugs. For example, an FDA-approved anti-cancer drug used to treat thyroid cancer (Vandetanib, developed by AstraZeneca) was originally discovered by Tirtha Das and Ross Cagan in a drug screen using fruit flies.

There’s currently no known cure for dementia. In October 2019, Biogen announced the finding of a promising drug (aducanumab) to treat Alzheimer’s disease. But unfortunately this drug simply slows down the disease progression and only in its early stages, so when Alzheimer’s is diagnosed it’s often too late. Niccoli’s lab collaborates with other research teams (Adrian Isaacs lab and Frances Wiseman lab) to speed up the translation of their findings in flies to more complex model organisms, such as mice and human cells.

When the children were younger it was harder [to juggle family and career] but I had a lot of support from family and we had an au pair living with us.

After doing a postdoc at the University of Cambridge studying cellular polarity in fruit flies, Niccoli took a career break to raise her two sons. She explains that returning to academia wasn’t easy, but it’s definitely possible with some planning and determination. Juggling motherhood and a demanding job can be challenging, but the time flexibility of a research career is a great advantage when you need to rush to daycare to pick up your sick child, for example. She says that having children inspired her to get involved in science outreach activities to inform the public about her research and to encourage the younger generations to pursue a career in science.

To learn more about Teresa Niccoli’s research and her experience as a woman in science, please watch the interview in our YouTube channel. And please don’t forget to subscribe! If you enjoyed this video, please go check our interview with Vivian Li, a researcher working on organoids and stem cells.