Illustration by Catarina Moreno (www.catarinamoreno.com)

Earlier this year, an Italian research team found that high doses of vitamin C in combination with immunotherapy, a type of cancer therapy that targets the immune system, could stop tumour growth in mice. Could the cure to cancer be as simple as taking vitamin C supplements during immunotherapy? And if yes, why hasn’t anyone shown this before? To answer these questions, we need to rewind and understand the rocky path of this controversial (but promising) research field .

Vitamin C and cancer

At a seminar in 1966, Linus Pauling, then a 65-year-old American biochemist and Nobel-prize laureate, mused that he wished he could live for 25 more years so he could keep learning about scientific discoveries. Soon after, he received a letter from one of the scientists in the audience promising that taking 3000mg of vitamin C daily would make that possible. Pauling blindly followed his colleague’s advice and later reported he felt “livelier and healthier”, and was also catching fewer colds, eventually upping the dose until he was taking 300 times the recommended daily allowance!

As the first person to win a Nobel Prize solo in two different categories, Pauling’s opinion carried a lot of weight. Soon, vitamin C was flying off the shelves. There was one problem with this miracle cure, though- there was no scientific evidence to back it up.

Despite the popular myth that vitamin C can prevent colds, a series of studies in the 1970s found that treating people with vitamin C before exposing them to cold viruses didn’t offer any protection against getting sick. Nonetheless, after these results came out Pauling doubled down and went as far as claiming that vitamin C could cure cancer. He based this idea on work done by a Scottish psychiatrist named Donald Cameron, who claimed that cancer patients treated with vitamin C did better than those who weren’t. Cameron was a very influential doctor but he was also criticised for using electrical shock therapy and experimental drugs in patients and prisoners without their informed consent (he also helped develop torture techniques).

Pauling decided to publish Cameron’s vitamin C findings in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, but the study was so flawed that this became the fourth paper submitted by a member of the academy to ever be rejected. It turns out that the patients treated with vitamin C were healthier at the start of the study, and the vitamin had nothing to do with their positive outcome. He continued to publish on vitamin C and cancer, even as other researchers were refuting his claims at every step.

Over the decade that followed, research into the anti-cancer effects of vitamin C yielded inconsistent results. The scientific community set this matter aside for a while, until a series of new studies published in the 1990s led to a resurgence of interest in the subject. This research looked at how cells process vitamin C, and suggested that the way it is administrated (oral vs injection) makes a huge difference to how the body reacts to it- and this could perhaps explain why early studies on vitamin C and cancer had contradictory results. Today, there are several clinical trials ongoing which are studying whether vitamin C can improve the efficacy of traditional cancer treatments like chemotherapy.

Now, a research team led by Alessandro Magri, Federica Di Nicolantonio and Alberto Bardelli, from the University of Torino and the Candiolo Cancer Institute (Italy), found that high-dose vitamin C can aid immunotherapy and stop tumour growth in mice. They discovered that vitamin C boosts the mice’s immune systems by regulating specific immune cells called T-cells, but whether these striking results can be translated to humans isn’t clear yet.

An orange a day keeps cancer away?

To look into this, the researchers injected human cancer cells into mice and waited for tumours to develop- this method allowed them to mimic several types of human cancer in mice, including breast, colorectal, melanoma and pancreatic cancer. When the mice had visible tumours, half of them were injected with a massive dose of vitamin C. The researchers then recorded how the tumours progressed with or without the vitamin. Remarkably, the tumours were much smaller in the mice injected with vitamin C. However, when the researchers did this experiment in mice with a weakened immune system, the vitamin C injections had no effect on tumour growth.

These findings suggest that vitamin C needs a functional immune system to slow down tumor growth- so the vitamin might be acting directly on immune cells. This hypothesis made sense with another finding: the researchers noticed that the immunocompromised mice had fewer T-cells. Maybe vitamin C helps T-cells destroy cancer cells in the healthy mice, they speculated. To test this, Magri and colleagues used antibodies to block T-cell production in healthy mice and then repeated the vitamin C experiment. They found that vitamin C injections could not slow down tumour growth in healthy mice lacking T-cells, which clearly shows that vitamin C somehow helps T-cells kill cancer cells. They now needed to understand how.

Vitamin C boosts the immune system- but you need a lot of it

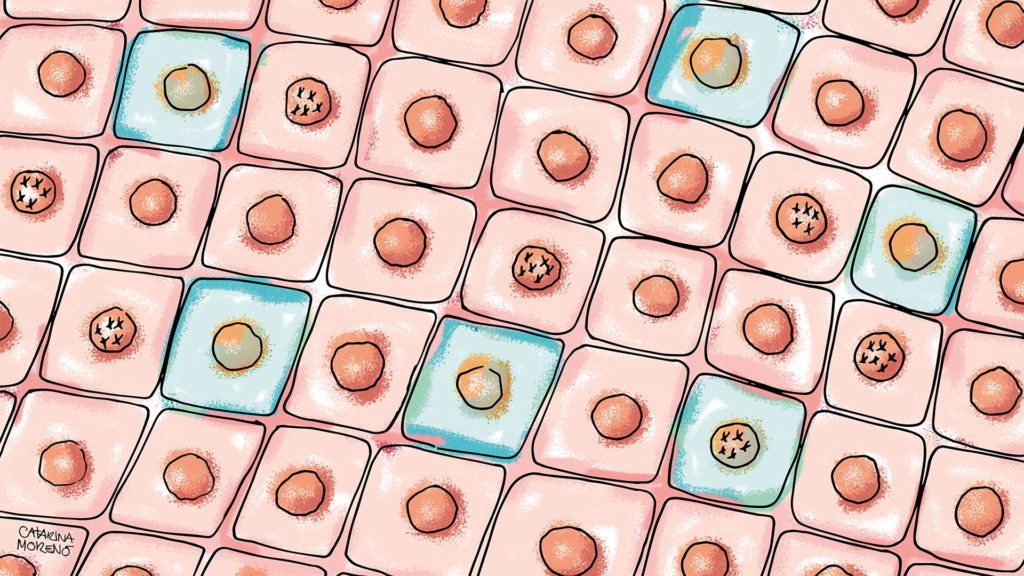

T-cell are produced in response to infection and disease. Proteins called checkpoints increase or decrease T-cell production to ensure we have just about the right amount- if we don’t have enough T cells, the body can’t fight diseases like cancer, but if we have too many, we may develop auto-immune diseases, such as type 1 diabetes for example. How does this link to cancer?

Cancer cells use clever tricks to escape our immune defences. Some cancers can boost the checkpoint proteins that stop T-cell production, so that eventually the body doesn’t make enough T-cells to stop tumour growth. Immunotherapies called Immune Checkpoint Therapy (ICT) target and inactivate checkpoint proteins in order to restore T-cell production in cancer patients. Can vitamin C further improve this type of immunotherapy by helping T-cells fight tumours? Bartelli, senior author in the study, said:

While vitamin C alone could slow down tumour growth, vitamin C in combination with immunotherapy shrank the tumours [until] they eventually disappeared.

The research team injected high-dose vitamin C into mice undergoing ICT therapy and indeed, in these mice the tumours shrunk even more than in mice treated with ICT or vitamin C alone, until they disappeared altogether- the mice were technically cured.

While in humans ICT unfortunately only works on cancers that attack the immune system, the vitamin C/ICT combination therapy tested in this study also slowed the growth of some types of mouse tumours that generally don’t respond to immunotherapy. These results are highly encouraging, but we shouldn’t start injecting high doses of vitamin C into cancer patients just yet. The dose of vitamin C used in this mouse study would be the equivalent of eating about 2000 oranges per day in humans! More research is needed to check whether people can tolerate such huge amounts of vitamins.

The authors of this study have initiated a phase I clinical trial to test whether cancer patients can tolerate escalating doses of vitamin C given in combination with ICT, and they hope to observe similar anti-tumor effects as those seen in mice. “This may also foster back translational research – so that we may be able to look at the impact of these combination therapies on human T-cells,” said Di Nicolantonio.

Almost 50 years after Linus Pauling’s first papers on using vitamin C to treat cancer, this study is the first to find that vitamin C may be helpful not on its own, but to boost immunotherapy in patients with healthy immune systems. Many boosting agents have failed in past clinical trials, but these findings suggest another promising candidate and the scientists involved are optimistic.

Nora Thoeng and Tori Delaine co-wrote this article.

Sources:

1- https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/cam/hp/vitamin-c-pdq#link/_14

2- https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/cancer-in-3- general/treatment/immunotherapy/types/checkpoint-inhibitors

4- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3462607/

5- https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2013/07/the-vitamin-myth-why-we-think-we-need-supplements/277947/

6- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC431183/

7- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1535610818303209

If you enjoyed reading this article, you might also like to learn about this study showing how our body is a mosaic of cells with genetic mutations.