Illustration by Catarina Moreno

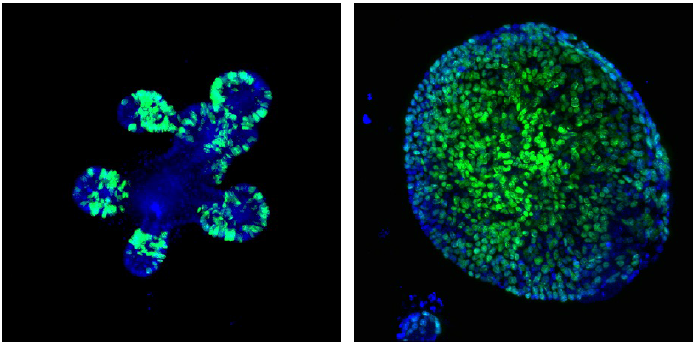

Organoids are 3D lab-grown tissues that behave and look like mini-organs. Vivian Li’s lab at the Francis Crick Institute in London, UK, uses organoids called ‘mini-guts’ to study stem cells and gastrointestinal cancer. I visited the Crick on a cold snowy day to interview Li and learn more about her research and what it’s like to be a woman in science (please see video below).

Vivian Li had always wanted to work on something that could improve or treat human diseases. When she was in high school back in Honk Kong, girls and boys were separated into different classes- girls had to study “Home Economics” (cooking, childcare, etc.), while boys studied Technology. This gender bias unfortunately prevented many girls from pursuing science and technology studies, but Li was determined to become a scientist and went on to complete a Molecular Biotechnology undergraduate degree.

When she was at university, there was a huge buzz around the human genome project, which had just been completed. Sequencing nearly the entire human genome was a tremendous breakthrough, and scientists thought they had unveiled the secrets of our DNA. Li was fascinated by the idea that although we now knew the sequence of over 20 thousand human genes, nobody had a clue what they were doing. She was excited about all the questions scientists could now explore with this massive amount of new information.

She decided to join a lab at the University of Hong Kong that studied gastrointestinal cancer and which had access to the genetic history of these patients. She investigated the role of genes in causing colonic cancer with the ultimate aim of finding new drug targets, and she was awarded a Gold Medal Prize for this work.

After completing her PhD, Li moved to the Netherlands to do her postdoctoral research at the Hubrecht Institute, and this is when she started working with organoids to study the molecular mechanisms controlling stem cells. But what do stem cells have to do with cancer? Li answers:

Stem cells and cancer in a way are connected. There are quite a lot of proteins in cells working together to control cell growth, particularly in stem cells, and these proteins are often also involved in cancer.

Stem cells are ‘special’ cells that don’t have a particular identity (they’re said to be ‘undifferentiated’) and that can divide indefinitely to give rise to more stem cells, but also to other kinds of cells, like neurons and skin cells. So every cell in our body originally came from a stem cell. Cancer cells have many things in common with stem cells, the most obvious being that they both keep on dividing and growing. Scientists think that cancer cells went ‘crazy’ and sort of regressed to their stem cell state. By studying how stem cells function and divide, we can also learn about cancer cells.

Li’s research is focused on the gut stem cells, which constantly grow and divide to replenish the cell loss in the gut tissue. This growth process has to be precisely controlled to make sure nothing goes wrong, because if it does… the stem cells continue dividing non-stop and become cancerous. She hopes her research can have clinical applications and that within a few years her organoids can be used to test medical drugs and to treat patients.

Besides wanting to be a researcher, Li also always wanted to have a family. She had her two children (age 3 and 1) while she was already running her lab at the Crick, and although she gets a lot of support from the institute, balancing work and family life can be challenging.

You need to be confident and believe in yourself. If you like your job then you will manage it by adjusting your work arrangements.

Li is a member of the Gender Matters in Science Committee of the Crick, a group of volunteers that aims to promote gender balance in the institute through networking events, workshops, and mentorship programs. She believes that established women scientists like herself need to share their experience and support other women at earlier stages of their careers.

If you would like to learn more about Vivian Li’s research and her experience as a woman in science, you can watch the interview on my YouTube channel (and please don’t forget to subscribe!).