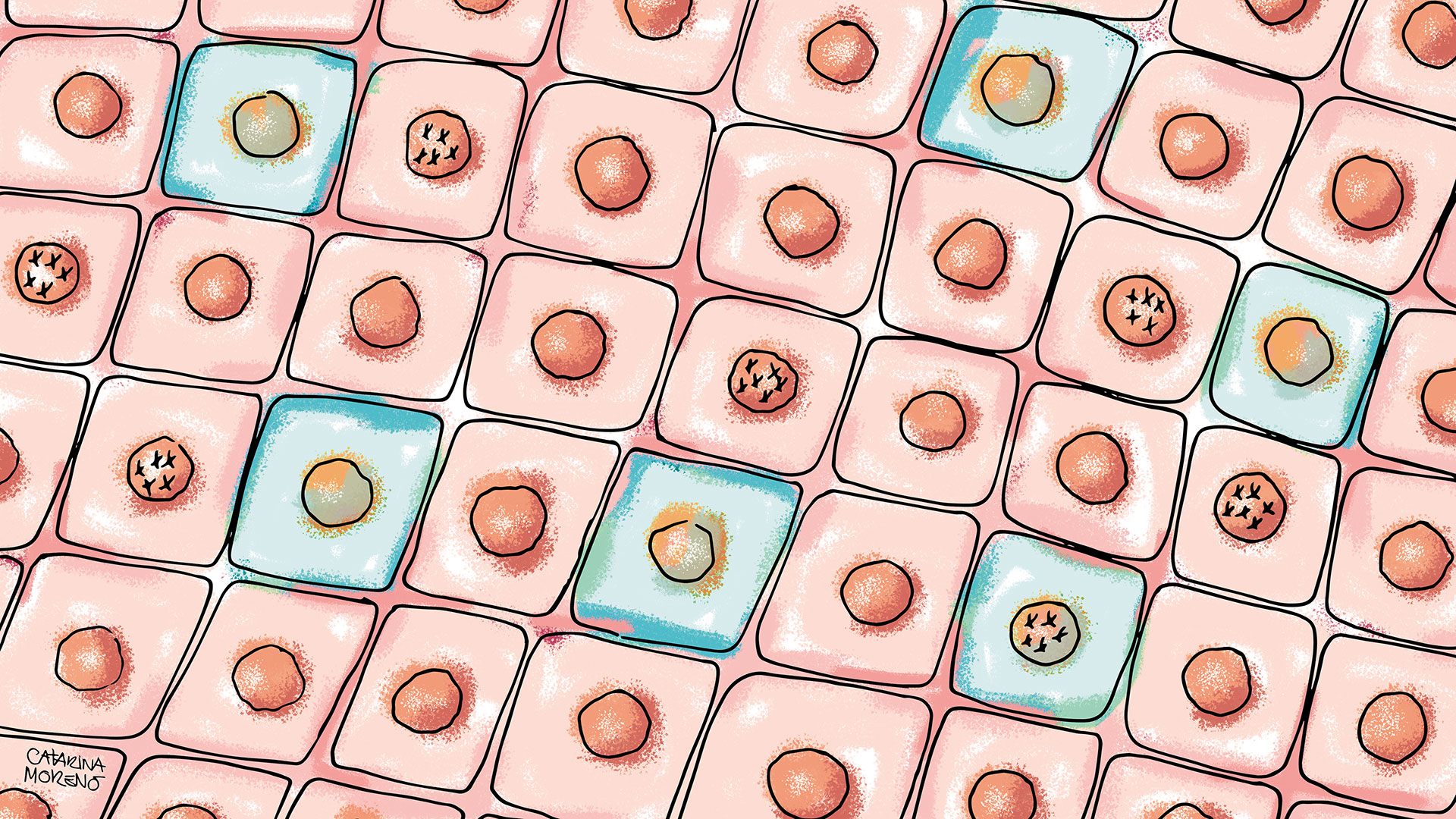

Illustration by Catarina Moreno ([email protected])

Genetic mutations make us think of the X-men, GMOs and… cancer. Cells with mutations in their DNA can go haywire, multiply uncontrollably and eventually form a tumour. Or maybe not. A recent study shows that our body is made up of patches of cells with genetic mutations- some may contribute to cancer, but most will probably not.

It has always been assumed that all the cells in the human body carry the same DNA, but over the past decades scientists started to unveil a different picture. Some tissues in our body are like a mosaic of cell clusters, each with a unique set of genetic mutations. How do these cell patches form?

Patchy tissues

Cells multiply by splitting into two identical daughter cells, but sometimes errors occur when new copies of DNA are being made- these are the genetic mutations we hear about. Genetic mutations can also be induced by environmental factors such as cigarette smoke or sunlight exposure. Some of these mutations are benign, but others can cause diseases like cancer. Normally, a robust protein machinery in our cells corrects these genetic errors, but sometimes this process fails. And when these cells divide, they transfer their mutations to the next generations of cells, eventually forming a cell cluster with a different genetic makeup from the surrounding cells in the tissue- this is called ‘somatic mosaicism’.

Previous studies looking at specific genetic mutations in microscopic tissue samples found mosaicism in the skin, oesophagus and blood. In the new study, a team of computational biologists at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston (US) decided to take a different approach to figure out whether mosaicism is widespread in all tissues of the body. Rather than analysing DNA from a few tissue samples, they used the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) database on RNA – DNA’s sister molecule. For proteins to be made, DNA molecules are first transcribed into RNA molecules, and often RNA will carry the mutations in the DNA template. Keren Yizhak, lead author in the study says

Our aim is to find exactly what is happening in the DNA from our work on RNA.

Yizhak and colleagues based their computational analysis on the assumption that RNA mimics DNA. They developed a new method, called RNA-MuTect, to spot mutations by comparing the RNA from a tissue sample to its known normal DNA sequence. Even though this strategy has some limitations, it allowed the researchers to screen data from 6,700 samples taken from 29 tissues in about 500 people, making it the largest study of the kind to date.

More mutations, more cancer?

The results showed that mosaicism can indeed be found in every tissue of our body, but to what extent depended on the tissue. Tissues where cells are constantly dividing or which are exposed to environmental factors (e.g. lung and skin) have a lot more mosaicism, the researchers found. This observation confirmed previous studies showing that sunlight and cigarette smoke could induce genetic mutations in skin and lung cells. Mosaicism also correlates with age- older people have more of the cell patches with genetic mutations.

Should we worry about all these mutations we carry in our DNA?

Yizhak and colleagues found that healthy tissues harboured cells with mutations in known cancer genes, such as a cell division regulator p53 (TP53 gene) and a developmental gene called NOTCH1. In fact, a third of people in the study had a mutation in cancer-promoting genes (called oncogenes), but they didn’t show symptoms of cancer. The authors believe that some of these cells may be at precancerous stages, but overall mosaicism appears to be a normal occurrence in healthy tissues.

Most cases are not cancerous… mosaicism is normal.

The challenge now is figuring out how to detect the early, often environmental, mutational events that progress towards disease. From being exposed to pollutants or sunlight as we age, we acquire harmless mutations in our normal cells too. So how to tell apart the precancerous mutations? The data in this study could be used in future research to compare normal, healthy cellular states of mosaicism from those causing disease. The National Cancer Institute has already launched the PreCancer Atlas project to search for potential pre-cancerous events on a larger scale. In the meantime, we can but admire the complex arrangement of cells within tissues revealed by this study- our body is a work of art.

References:

Donald Freed et al. Somatic Mosaicism in the Human Genome. Genes (2014).

If you enjoyed reading this article you might also like this interview to a cancer researcher. Vivian Li’s lab at the Francis Crick Institute in London, UK, uses organoids called ‘mini-guts’ to study stem cells and gastrointestinal cancer.