Illustration by Rosa Mourlan ([email protected])

What drives success in academia? Only very few people become presidents, create a million-dollar business empire from scratch, or win a Nobel Prize. So what makes these people special? Countless social studies show that a child’s economical background and social environment are critical for shaping their future life. Genes and personality play a small part, if any, in determining success. As a parent, I try to give my children every possible opportunity for a great start in life. So I’m curious to learn what specific aspects of the “social environment” may increase their chances of success in adulthood. Of course the definition of ‘success’ is relative. For me a successful life is simply a happy life, and this has nothing to do with having a high-profile job, a chunky salary, celebrity, or anything of the sort. But my aim in this article was to figure out what drives academic achievement specifically. And since the pinnacle of academic success is winning a Nobel Prize, I decided to analyse the life of a scientist who despite having all the odds against her was awarded not just one, but two Nobel prizes: Marie Curie.

Who was Marie Curie?

Marie Skłodowska Curie is the second most famous scientist in the world (after Albert Einstein) and undoubtedly the most famous female scientist. If we look at her academic track record, it’s not difficult to understand why. Marie Curie was the first woman to earn a PhD in physics, the first female professor at the prestigious Sorbonne university in Paris, the first woman to win a Nobel prize in science and the first person (man or woman) to receive TWO Nobel prizes. To this day, she is the only person to have won two Nobel prizes in different scientific disciplines (physics and chemistry).

These achievements are all the more impressive when we put them into a historical context. When Marie Curie was a young adult, women were not allowed to go to university except in a handful of countries, they couldn’t even vote. Their fate was set from birth: becoming wives and mothers. So why did a Polish woman at the end of the XIX century pursue a research career in physics and devote her life to science? How was she able to excel scientifically within an academic community made entirely of men? And finally, how could she accomplish so many achievements and also raise two successful daughters, one of whom was also awarded a science Nobel prize?

In this biography I try to answer these questions. The facts described here are mostly (but not exclusively) based on a biography written by Marie’s daughter, Eve Curie, but the interpretations are my own. I really enjoyed this book and I strongly recommend it. Eve’s account of her mother’s life is obviously a little rose-tinted. Nevertheless, I believe that to get to know Marie, the woman, it makes sense to listen to the people who were closest to her.

Childhood: role models and nurturing curiosity

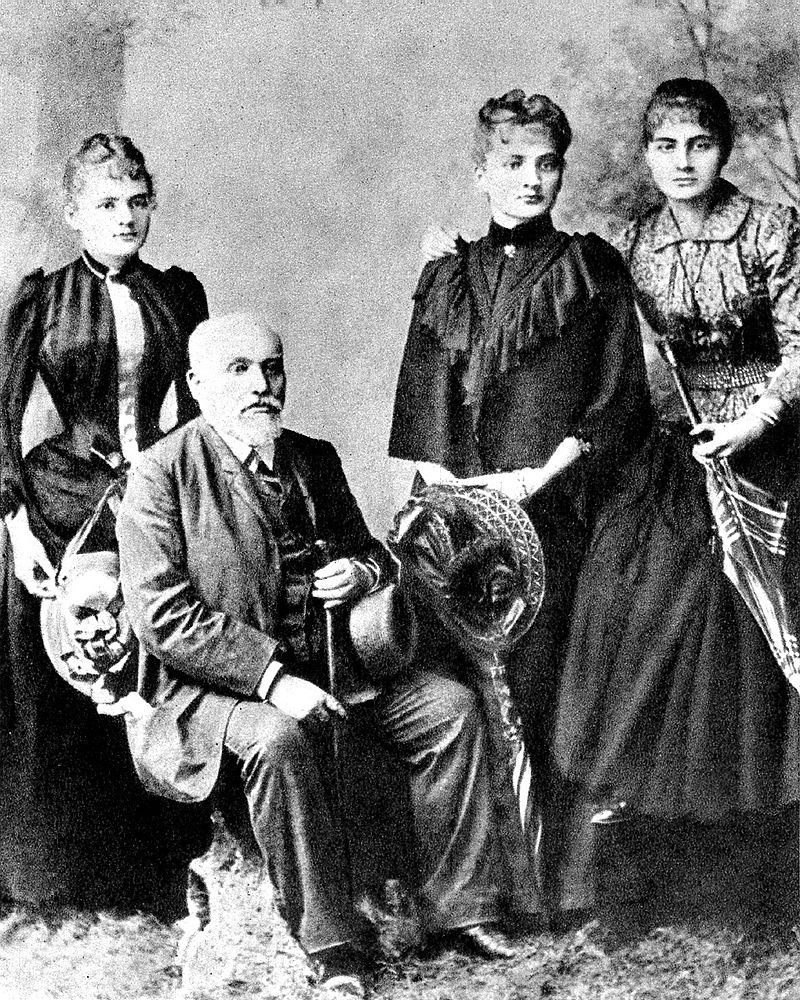

Marie Curie, née Marya Salomea Skłodowska, was born on November 7th 1867 in Warsaw, Poland. She was very close to her four elder siblings, and both her parents were caring and devoted to their children. The Skłodowska family was rather unusual in that boys and girls were treated equally. Marie’s mother received an impeccable education and was dedicated to her teaching career, even after the birth of her children. Although Marie lost her mother at a young age, she was undoubtedly an important role model.

Marie’s father, Władysław, also a teacher, was very passionate about science. Leisure and fun for him consisted of reading books or research papers and solving physics or maths problems. Studying wasn’t forced in the Skłodowska family, but it was encouraged. Władysław nurtured his children’s curiosity by allowing them to play with his collection of scientific gadgets and giving them unlimited access to his vast library. Solving complex algebra problems or reading a German philosopher was something rather normal for Marie and her siblings. So while other girls her age were concerned about boys, dresses and balls, she was dreaming of going to university to study science.

From her parents Marie inherited an insatiable curiosity and a love of learning, but also a despise for luxury or material things. She did have her share of fun and was known to be a good dancer, but she simply enjoyed learning more. And because her parents trusted her abilities and potential, and encouraged her to pursue her ambitions, she became a confident woman.

Determination and work ethics

This stimulating and warm family environment paid off: the Curie children finished high school with the highest honours and spoke five languages fluently. Marie’s brother went to medical school at the University of Warsaw, but women were not admitted and Władysław couldn’t afford to send his daughters to study abroad. After all her hard work in school, this was a big blow to Marie’s morale. The premature death of both her mother and sister Sofia from disease also deeply affected her. At 15 she became depressed, but a year spent in the countryside got her back on her feet.

With renewed energy, Marie and her sister Bronya worked as tutors to earn money for college while attending the clandestine “Floating University” in Warsaw. They eventually realised that their miserable salary would never be enough to pay for their studies in Paris. But Marie was determined. She put her dreams on hold for three years to work as a governess for a rich family living in the remote Polish countryside. During those lonely years she studied by herself every day and worked tirelessly to prepare for the Sorbonne university exams. She had an extraordinary work ethics (taught by her father) and remained focused on her goal. Except when a boy came along.

Marie and her employer’s eldest son fell in love and desperately wished to get married, but his parents weren’t having it. Despite Marie’s faultless education, which was by far superior to their own, the boy’s parents wouldn’t allow him to marry a mere governess. Marie almost gave up her dream of studying science for love- had their marriage gone ahead, she would have become a teacher or maybe even a housewife. But in the end, painful as it was, the rejection gave her an injection of energy and renewed motivation to follow her ambitions. She went back to Warsaw and worked as a tutor and governess for two more years, until she finally had enough money to pay for her studies. At 24, Marie moved to Paris to study science.

College: passion and drive

She decided to take a physics degree but soon began to prefer the experimental subjects. Marie loved being in the laboratory. She was the only woman in her course, but although she attracted a lot of male attention, she never lost focus in her studies. Her heartbreak back in Poland taught her to never again allow anything to distract her from reaching her goals.

When not in class, Marie was either studying at the library or in her miserable room. Cooking was a waste of time and money in her opinion, so she lived on bread and tea. Her passion pushed her to exhaustion and malnutrition, and she occasionally fainted in class. Nevertheless, she finished first in her physics degree and then won a Polish scholarship to take a mathematics degree, which she finished second. Marie’s original plan was to return to Poland after graduating to look after her father, but two things made her change her mind: falling in love with science and with Pierre Curie.

Marie and Pierre Curie met during her last year at university. At that time, she was doing research on the magnetic properties of steels, which was her first “proper” job as a scientist. Since her laboratory didn’t have all the equipment she needed, a friend suggested she should ask Pierre for some lab space. He was an established physicist at the School of Physics and Chemistry, and while it is said he was immediately attracted to Marie, his affection wasn’t reciprocated. Still cautious with love, she rejected his marriage proposals for over a year, clearly more interested in science than in becoming a wife, but eventually she agreed to marry Pierre. The couple had a very simple civil wedding (they were both “free thinkers”, meaning, atheists) in the suburbs of Paris with their closest family and friends. Marie wore a black dress because she wanted to reuse it in the laboratory. She famously said to her sister Bronya:

I have no dress except the one I wear every day. If you are going to be kind enough to give me one [for the wedding], please let it be practical and dark so that I can put it on afterwards to go to the laboratory.

Balancing career and family life: support and resilience

Getting married didn’t affect Marie’s career, but it added an extra layer of difficulty. Pierre supported his wife’s ambitions and saw her as an equal, scientifically and intellectually, but at home the traditional gender roles weren’t questioned. Marie took sole charge of the house chores and finances, and she even learned to cook to please her mother-in-law. After working eight hours in the lab, she was an attentive wife and an assiduous housekeeper, and then she put on her scientist hat again and studied late into the night. She was tired but happy. When she fell pregnant, Marie carried on working in the lab and doing her chores at home, even though she felt exhausted and nauseous throughout the pregnancy. Her first daughter, Irene, was born in September 12th, 1987.

Marie was a devoted mother. She tried very hard to breastfeed Irene, and felt extremely guilty when she was forced to stop following her doctor’s orders. The young mother was delighted with her irresistible baby, yet she couldn’t wait to get back to the lab. And soon she did, just a few weeks after giving birth. Despite struggling to juggle her research work, looking after her newborn and doing the housekeeping, choosing between family and career never crossed her mind. How could she “have it all”? Childcare. A nanny took care of the baby during the day, and her doting father-in-law was always on call to look after the child when needed. Marie wrote to her sister Bronya:

It became a serious problem how to take care of our little Irène and of our home without giving up my scientific work. Such a renunciation would have been very painful to me, and my husband would not even think of it.

Ambition and hard-work

A doctorate degree was the next logical step in Marie’s career, and it was something she really ambitioned deep in her core. Rather than pursuing an “easy” research topic, she wanted to do exploratory science. This decision was driven by her curiosity, but also by ambition. Exploratory research is riskier, but it’s also the kind that generally leads to groundbreaking discoveries. She wanted to do something big. She spent weeks reading papers before carefully choosing the topic of her thesis, and finally decided to study a strange new type of “radiation” released by uranium that had been recently discovered by Henri Becquerel. At the time X-rays were the trend, so Becquerel’s radiation was largely ignored by the scientific community. Marie had a hunch this enigmatic radiation would turn out to be something important. And she was right.

She soon discovered that uranium atoms spontaneously released the strong energy rays Becquerel had detected. This was bizarre, unlike anything else. She wondered whether other elements had such strange properties… After analysing all the other elements known at the time, she discovered that thorium also spontaneously released this type of energy, which she coined radioactivity. Marie then noticed something weird: some of the samples emitted a lot more radioactivity than they should. She suspected they must contain a new unknown element in them, one much more radioactive than uranium or thorium. The young couple were extremely excited with this hypothesis, but their colleagues just assumed Marie had made an experimental error. She was only a woman after all… Marie ignored the sceptical criticism and carried on with her research, confident she was about to make an important discovery.

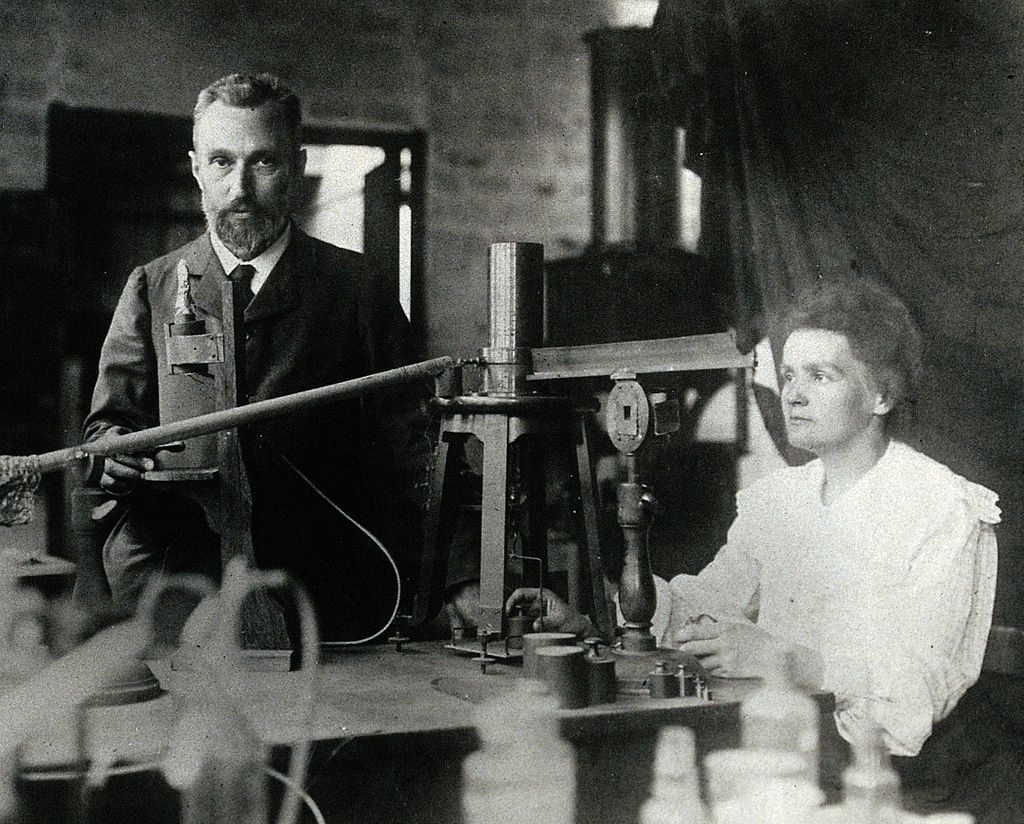

At this point, Pierre put aside his own research to help Marie in the lab. This was the beginning of a fruitful collaboration that would result in a Nobel prize in physics awarded to Pierre, Marie, and Becquerel. The couple worked incessantly for about four years in a mouldy shed of the School of Physics which had previously been used in anatomy lessons to dissect corpses. These were the happiest years of Marie’s life. Side-by-side husband and wife worked until exhaustion, and in the summer holidays they renewed their energy by completely disconnecting from work and indulging in dolce far niente for at least a month.

Marie developed a new method to isolate the mysterious radioactive element from uranium ore (called pitchblende). This was a tremendous task, but her persistence paid off. She found not one, but two new radioactive elements, which she named polonium (after her native country) and radium. More than a ton of pitchblende was necessary to extract just a few decigrams of radium, and Marie did this work on her own. Pierre and Marie published dozens of papers during these prolific years, and soon several other scientists began working on radioactivity. A new science was born.

In December 1903, just a few months after successfully defending her thesis and becoming the first woman to earn a PhD in France, Marie became the first women to be awarded a Nobel Prize.

The bitter taste of success

The discovery that radioactivity could treat tumours (now we know radioactivity actually causes cancer) turned the couple into celebrities. However, despite their fame and Nobel prize, they were struggling financially. They were both forced to take extra jobs tutoring and teaching to afford a housekeeper, so they could work long hours in the lab. Pierre was finally promoted to professor at the University of Paris after threatening to accept an offer for a professorship at the University of Geneva, in Switzerland. He didn’t receive any extra funding for the laboratory though, only promises. And Marie? After working unpaid for several years and winning a Nobel prize, she was promoted to… laboratory assistant.

They were always tired and often ill, likely due to the exposure to radioactivity. When Marie became pregnant of her second child, she was forced to spend the last months of pregnancy in bed rest, which left her very depressed. But the arrival of her baby daughter on December 6th, 1904, who she named Eve, brought her joy again. She would have relative peace for a couple of years until Pierre died tragically in an accident in 1906.

Sexism, xenophobia and another Nobel Prize

Marie was devastated by her husband’s death. Her daughter Eve writes that it seemed that Marie “had already abandoned the living”. Still, she carried on working, always. Shortly after her husband’s death, Marie was offered his professorship at Sorbonne, in this way becoming the first woman to teach at the prestigious university. Life got complicated, though. While her husband was alive, Marie was somehow protected. They had always worked as a team, and Pierre made sure Marie received fair credit for their discoveries. But now that he was gone, Marie was an easy target for those who believed a woman’s place is in the kitchen.

In 1910 she narrowly lost a seat at the French Academy of Sciences, despite her faultless academic track record, a Nobel prize, and the support of many colleagues. None of this mattered, because she was a woman. After her defeat the academy held another vote to decide whether women should ever be admitted, and the ‘no’ won with a large majority (90 against 52). A few decades later the academy would also reject Marie’s daughter, Irène Joliot-Curie, who won a Nobel prize in chemistry for the discovery of nuclear fission in 1935.

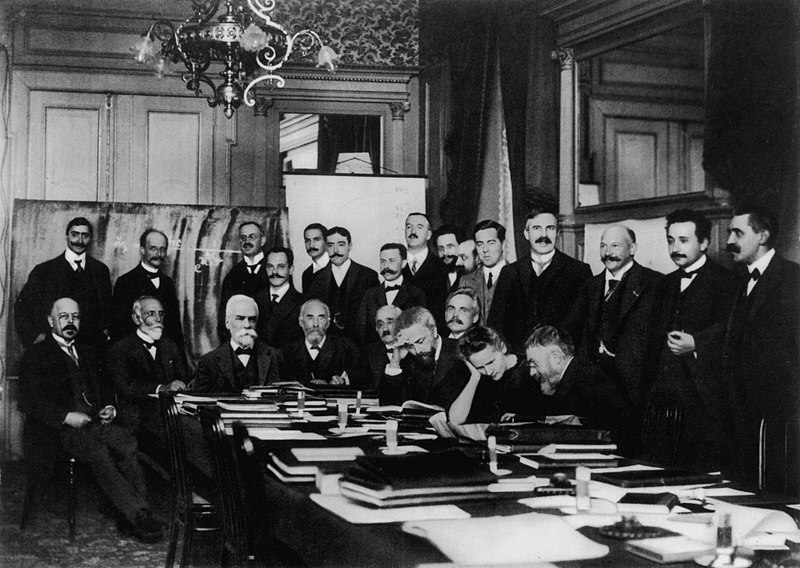

Marie’s ordeals continued for a number of years. After her academy rejection, a newspaper got hold of some of her letters to Paul Longevin, a long-time friend and colleague with whom she fell in love with years after her husband’s death. Paul was a married man, so their affair was a scandal. Sexist, xenophobic and even anti-semitic attacks (she wasn’t Jewish) by the press tormented her. When Marie returned from the famous Solvey Conference in Brussels, where she was the only woman among 23 men, she was surprised by had an angry mob waiting in front of her house. Some of her colleagues and former admirers asked her to leave the country. On the other hand, Paul’s reputation remained intact, even though he was being publicly unfaithful to his wife.

Amidst all this, Marie was singly awarded a Nobel prize in Chemistry for her discovery of radium and polonium, which made her the first person in the history of the Nobel Prize to receive two awards. This unprecedented achievement was unfortunately clouded by her romantic affair. The Swedish Academy of Sciences even asked her not to attend the award acceptance ceremony, claiming in a letter that if the affair had been publicly exposed sooner, she wouldn’t have been awarded the prize. She went to Stockholm to receive her prize anyway, and although she was normally extremely humble in her speeches, in this occasion she mentioned very clearly that the isolation radium was work conducted by her alone. She wrote in letter to the Swedish Academy:

I believe that there is no connection between my scientific work and the facts of private life… I cannot accept the idea in principle that the appreciation of the value of scientific work should be influenced by libel and slander concerning private life.

Conclusion: what makes a Nobel Prize winner

Marie Curie was an exceptional woman. After pocketing her second Nobel Prize, she accomplished many other great achievements. Besides raising money and pulling the strings to build research institutes in Paris and Moscow, she produced countless research articles and mentored dozens of students, including many women. During the Great War, Marie saved the lives of thousands of soldiers by distributing X-ray machines to hospitals and providing training to operate these machines. But probably her greatest achievement was raising two successful daughters: Eve, a best-selling author, and Irène, who followed her mother’s steps and became a physicist and a Nobel Prize laureate. Marie remained stubbornly active in the lab until her last days, even when she was frail and nearly blind from radioactivity exposure. She died on July 4th of 1934 surrounded by her family, leaving a tremendous legacy: she paved the way for women in science and showed everyone that women can.

This is what you can read in any of her many biographies, but I believe Marie Curie’s story tells us much more. She wasn’t a superwoman. She was burnout and depressed at times, she struggled to balance career and family life and often felt guilty for not being around her children enough. And like any human, she needed long holidays to recharge… But Marie was ambitious, confident, driven, resilient, passionate and hardworking. These fundamental qualities were the foundation of her academic success. And such personality traits typically develop during childhood. Marie was confident and ambitious because she was raised like a boy, basically. She grew up free of gender bias at home, so she believed she could do anything she wanted, as long as she worked hard. Unfortunately life isn’t that simple, as she would quickly discover. Women face many hurdles that can’t be overcome just with passion and self-belief.

Marie would have been forced to abandon her research career when she became a mother had she not been able to hire a nanny and a housekeeper. The couple had to take extra teaching jobs to afford these rare commodities and work longer hours in the lab, because Pierre didn’t share the burden of childcare or house chores. On the other hand, in the laboratory he saw his wife as an equal, and he made sure she received the credit she deserved. If he hadn’t pressured the Swedish Academy, Marie would have been snubbed of her first Nobel prize. She had to work exceedingly hard and prove her scientific worth for many years until her peers started respecting her as an equal.

Marie was probably a genius, but even the most outstanding individuals can’t succeed if not given equal opportunities. How many Marie Curies and important scientific discoveries have we lost to discrimination and bias?

References:

Eve Curie “Madame Curie” Da Capo Press (2001 Edition)

Shelley Emling “Marie Curie and her Daughters” Palgrave Macmillan (2013 Edition)