Illustration by Catarina Moreno ([email protected])

Would you return a lost wallet to its owner? And how about if the wallet had 100 dollars inside? Though a lost wallet experiment might sound like a concept for a YouTube video, a team of researchers recently used this classic dilemma to study civic honesty. Surprisingly, their results show that people are more likely to return a wallet with money inside than one without.

Honesty is the basis of a functional society, but when it comes to money-making opportunities some individuals are tempted to put honesty aside – whether it’s about deliberately failing to notice an undercharged restaurant bill, or more important violations like tax evasion. But why are even the most honest people sometimes tempted to bend the rules? And is it always about money?

Several studies have looked at what nurtures or discourages honest behaviour – for example, cultural norms or influence from family and peers – but few studies have asked whether financial temptation affects civic honesty.

In the new study, a research team of economists from the US and Switzerland conducted a huge “lost wallet” experiment involving 17,000 people- the largest study of its kind. The researchers went ‘undercover’ to public institutions (e.g. hotels, banks, post offices..) and asked an employee at the front desk to return a wallet they had found on the street. They said to the person “Somebody must have lost it. I’m in a hurry and have to go. Can you please take care of it?”. The exact same experiment was repeated in 355 cities across 40 countries in all continents, except Antartica.

But there was a twist. All the wallets contained the same items (a shopping list, a key, business cards with the email address of the fake owner), but only half of them had money inside- about US$13.45 in the local currency. But did this matter?

Can financial temptation tip our moral scale?

For the next 100 days the team checked how many employees attempted to contact the wallet owner by email, and it turns out that overall people were more likely to return wallets containing money. Michel Maréchal, an economist at the University of Zurich, Switzerland, and author in the study says:

We hypothesised that […] a higher incentive to steal would lower honest behaviours. Much to our surprise, we observed the opposite effect.

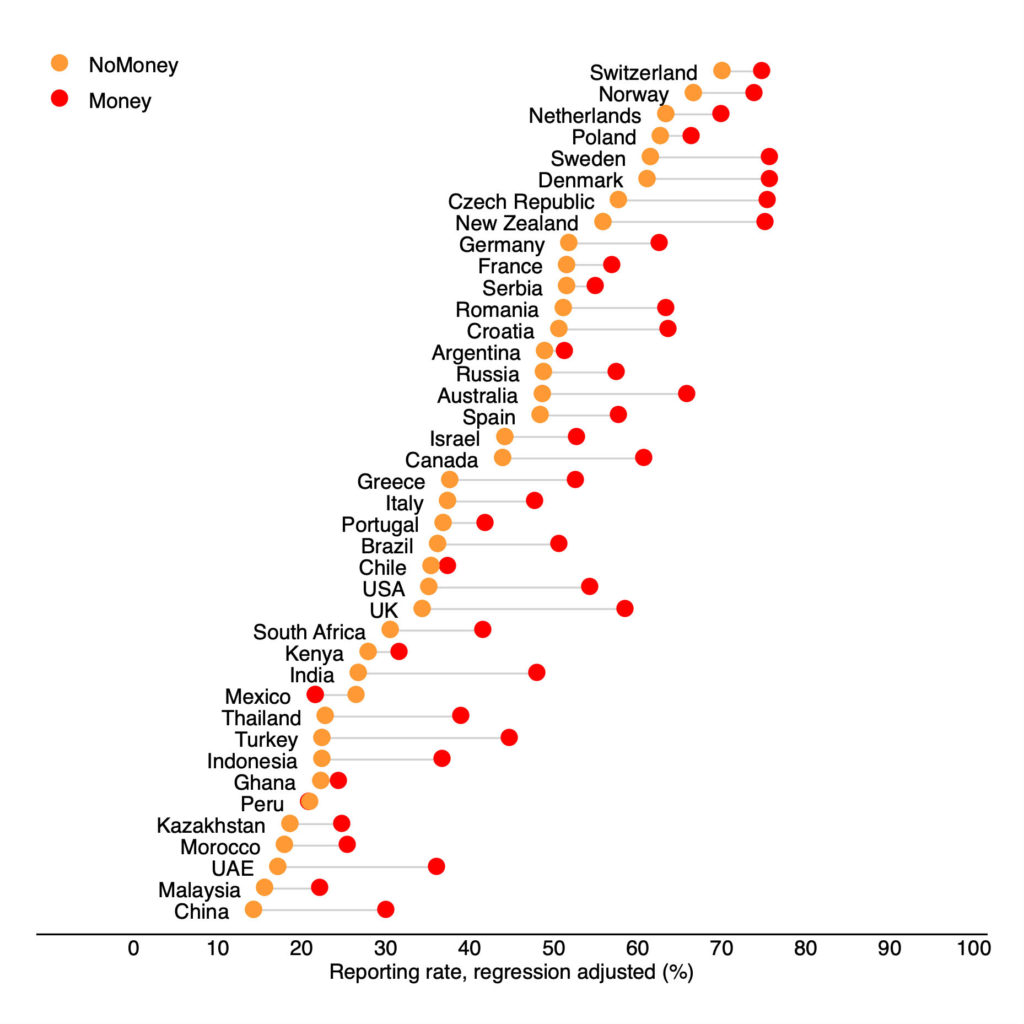

On average, about 51% of lost wallets with money were returned to the owner, compared to only 40% of wallets with no money. Astonishingly, these results were consistent in 38 out of 40 countries, although the return rates varied between countries. “Citizens are generally more likely to report a lost wallet with rather than without money,” explains Christian Zünd, a researcher at the University of Zurich, Switzerland, and senior author in the study. “The results also remained the same when we controlled for other factors such as the age or gender of the person who received the wallet.”

But it gets even more interesting.

The researchers were curious to find out what would happen if the wallets had more money – maybe the original amount was too small of a temptation. So they repeated the experiment (in UK, US and Poland) but this time some wallets had about US$ 94.15 inside. To their surprise, people were even more likely to return the wallets – a whopping 72% of wallets containing US$ 94.15 were returned, when compared to only 46% of wallets with no money.

This is exactly the opposite of what the experts expected. Classic economic models based on self-interest suggest that honest behaviour decreases as the material incentives increase- more money, more temptation to steal. Then, why? To try and make sense of their results, the researchers conducted more experiments. For example, they found that people were more likely to return a wallet with a key inside, regardless of whether or not it had money. This means they generally cared about the wallet owner- losing a key is a pain, worst than losing a few dollars- so it was purely an altruistic act.

But if the wallets were returned only by altruism, the amount of money in them shouldn’t make a difference, right?

To figure this out, the team conducted a survey and asked people why they returned the wallets. Most said that not returning a wallet with money would feel like stealing, and the more money, the stronger the feeling of wrongdoing. So these individuals didn’t act just by altruism, they were also concerned about their self-image- we don’t want to be dishonest.

Civic honesty across countries

We could easily assume that in richer countries people would be more likely to return a lost wallet, yet this isn’t always the case. In the United Arab Emirates for example, which is one of the richest countries in the world, only about 36% of wallets with money were returned. The authors considered many variables – economical, geographical, religious beliefs, and even linguistics – and found that cross-country variations in civic honesty could be largely explained by the countries’ national education, political institutions, and also cultural values. For example, countries with strong family values that often prioritise loyalty towards one’s own group, rather than towards strangers, tend to have lower rates of returned wallets. Alain Cohn, from the University of Michigan, USA, and first author in the study says:

Historic cultural factors can also explain part of the variation, specifically cultural factors that emphasise the importance of social obligations towards strangers, that is, obligations that go beyond one’s immediate in-group, such as family and friends.

Although this is a carefully conducted study, the chosen methodology has some limitations. The wallet drop-offs were done in institutions rather than on random public streets, which narrows the section of the population to citizen with medium-income living in bigger cities. The authors claim they chose these institutions to ensure the employees had access to computers and could use emails. However, emails might not be the best option in countries like China, where WeChat or other platforms are more commonly used. Zünd explains “We needed a way to identify each individual wallet that was reported back to us, which meant creating over 17,000 unique email addresses. It would be virtually impossible to create 17,000 unique phone or social media accounts […]”

Conclusions

Civic honesty is more complex than previously believed, and it’s difficult to distinguish altruistic behaviours from law-abiding behaviours. This study shows that the old saying “finders, keepers” isn’t necessarily true, even when there’s a financial temptation. This serves as a lesson that we should be less cynical and have more faith in humanity.

References:

Alain Cohn et al. Civic honestly around the globe. Science (2019)

Rodolfo Barragan and Carol Dweck. Rethinking natural altruism: Simple reciprocal interactions trigger children’s benevolence. PNAS (2014)